Are there British Gatekeepers?

What can UK Conservatives learn from Pierre Poilievre?

One of the oddities of the modern news cycle is how quickly everyone becomes an expert on the topic of the day.

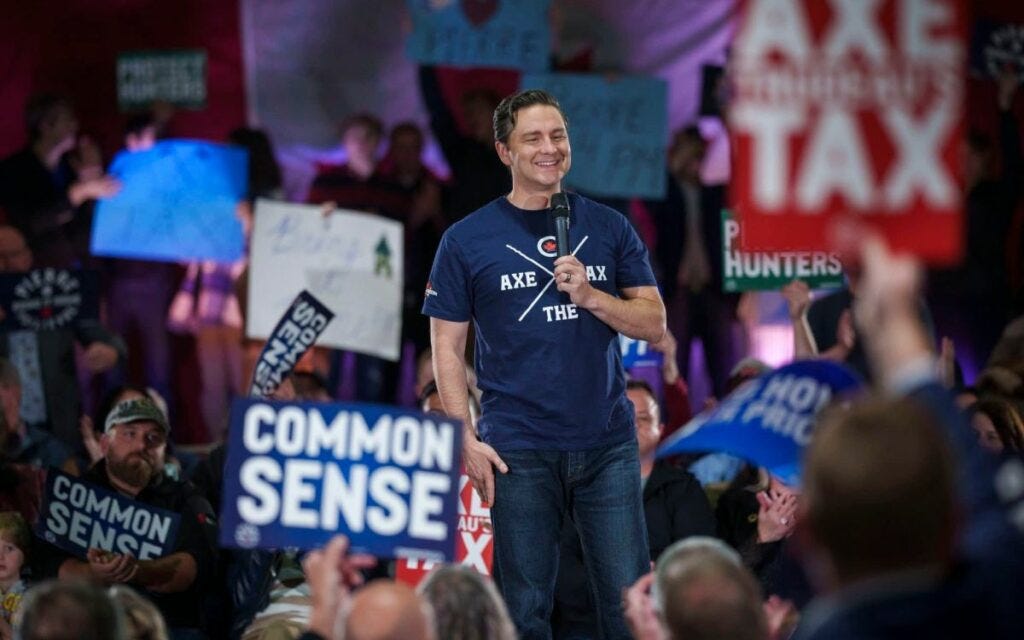

By early 2025, Pierre Poilievre will dominate the political conversation, drawing widespread commentary on the lessons the right can draw from his rise.1 Why? Because while the UK Conservative Party grapples with irrelevance, he’s on track for a 20-25 point victory, with over 220 seats out of 338—a majority government the Conservatives haven’t seen since 2011.

He’s not had the easiest ride either. In 2011, they won thanks to a historically weak opposition,2 destroyed by one of the greatest political ad campaigns ever.3 In 2024, Poilievre faces Justin Trudeau—battered, bruised, and unpopular, but still one of the all-time greats of Canadian politics. Back in 2013, he inherited a Liberal Party with just 36 seats and took them to 184 in two years.4 Since then he has won again (2019) and again (2021). If there are two things that are common amongst Conservative campaign professionals, it’s a desire to get Trudeau out, and a respect for his campaigning prowess.

Now, however, with ministers resigning - including recently the Finance Minister just before the economic statement,5 6 an election is on the cards - likely following a January confidence vote. Even if Trudeau somehow hangs on,7 it is almost certain that the next Prime Minister of Canada will be Pierre Poilievre.

What can the right learn from Poilievre?

The Anglosphere loves importing lessons from victories abroad. Boris Johnson’s 2019 win inspired Canadian Conservatives enough to bring Brits over for the 2021 election.8 Similarly, UK Labour found lessons in Australia’s 2022 Labor victory—and, amusingly, the Democrats allegedly learned from the UK’s 2024 election.9

We can already see this happening. In the recent Conservative leadership contest,10 one candidate directly compared themselves to Poilievre and sought to present themselves as the British equivalent, whilst nearly every piece of digital content that the Canadian Conservatives put out was shared across campaign teams with “Can we do something like this?”

So what lessons can the right learn from Pierre? I think there are three ways of thinking about this - with very different implications. They are - in order:

Pierre - the right man at the right time:

Pierre - the communications guru:

Pierre - the prophet.

All have very different implications. Put simply, if the first is right - it can’t be aped. If the second is right - it can be copied regardless of circumstance. If the third is right, Poilievre is a sign of something much bigger to come.

I’ve spent a while on both British and Canadian politics. I just finished being a Spad in the former, as well as writing a review of the 2019 election, and doing plenty of work on 2024. I also ran the polling and seat projections for the 2021 Canadian election. So I have a few thoughts.

But before diving into what makes Poilievre unique, it’s important to understand the context in which he emerged—a turbulent period for Canada’s Conservatives.

Canadian Conservative politics since… 2015?

I’ll inevitably gloss over vital details - but it’s worth noting that the Conservative Party of Canada starts in a very different place from the UK Conservative party.

Since being ousted in 2015, Canada’s Conservatives have faced the challenges of opposition, cycling through leaders with different strategies to reclaim power. Andrew Scheer, elected in 2017, positioned himself as a “Real Conservative,” leaning on Harper-era continuity while moderating some social positions. His 2019 campaign gained 26 seats but failed to convert a popular vote lead into a victory, largely due to massive margins in safe Prairie ridings.11

Following Scheer’s resignation, Erin O’Toole emerged as leader in a Covid-disrupted 2020 race, notable for Poilievre’s absence. O’Toole campaigned as a “True Blue” Conservative but quickly pivoted to the centre, adopting moderate positions on carbon taxes, guns, and abortion. This alienated parts of the Conservative base while failing to ultimately attract enough swing voters. The 2021 election, called by Trudeau to secure a majority, left the Conservatives unchanged in seat count. They narrowly won the popular vote again but lost support in strongholds, making only modest gains in Atlantic Canada and rural Ontario/BC.12 The caucus, frustrated with O’Toole’s approach and catalyzed by the Trucker convoy protests, ousted him in early 2022.

Pierre Poilievre’s leadership marked a decisive turning point. Winning 70% of the vote in the first round and securing control in 330 of 338 ridings,13 he gained an unprecedented mandate to reshape the Conservative Party. Poilievre began his leadership focusing on economic frustration, institutional reform, and anti-elite messaging. His rise coincided with growing dissatisfaction with the Liberal government, positioning the Conservatives as a vehicle for broad discontent. For a UK audience, the best analogy might be Boris Johnson in 2019: building on the groundwork of predecessors but rejecting their compromises to deliver a decisive, populist mandate.

The difference, of course, is that Poilievre isn’t in government yet. But he will be soon, prompting the question - what lessons can UK Conservatives draw from his rise?

1. The right man at the right time:

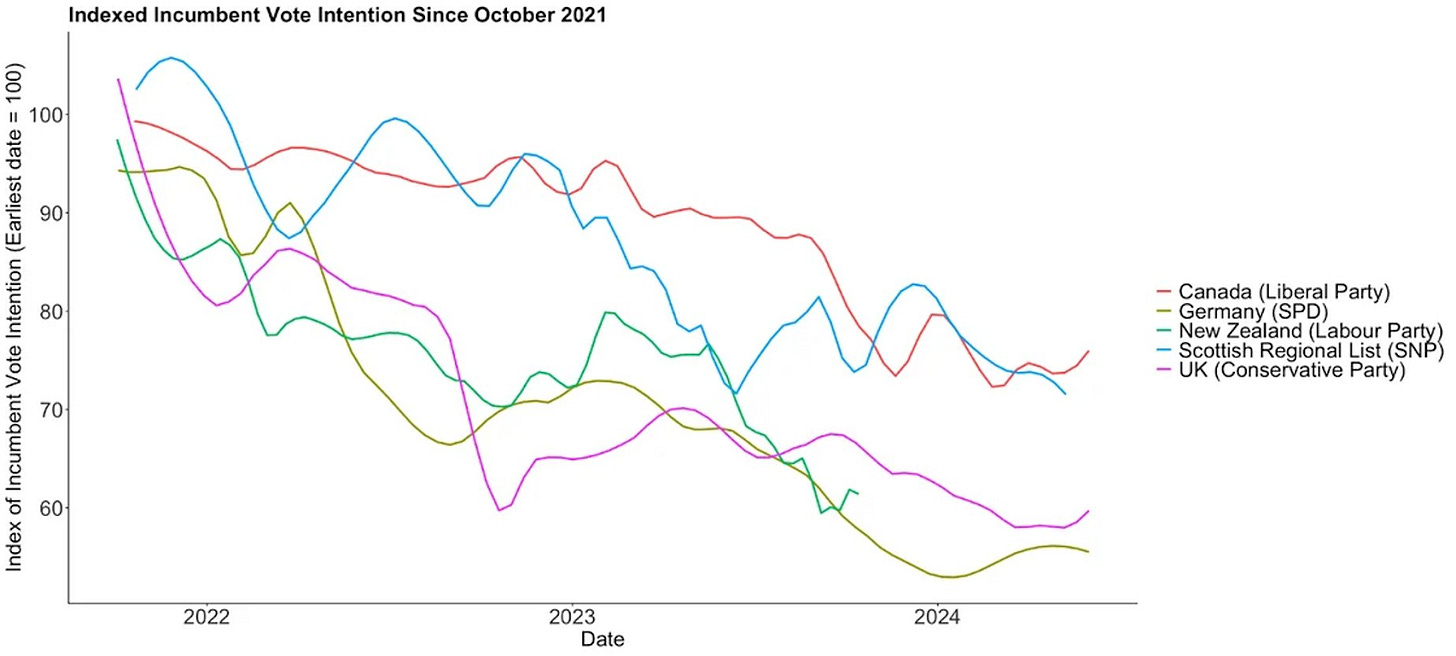

Put simply, Poilievre might be in the right place at the right time. He is leading the opposition as incumbents across the world have toppled. The best depiction of this is from my former colleague James Breckwoldt and some recent work we did for Onward:14

The tl;dr is that incumbents are getting smashed everywhere,15 mostly as a consequence of record inflation from the combination of global conflicts and the unwinding of Covid support. In Canada, Poilievre is going up against a Prime Minister with record unpopularity, and who - unlike in 2021 when people in my focus groups disliked him but trusted him, is now a huge drag on the ticket. He is also - much as Johnson did - building on gains in non-traditional Conservative seats which didn’t tip last time, but might this time.16

Notably, this does not just mean that anyone could be in Poilievre’s position. He is also the right man - specifically an inflation hawk at a time where the Government is viewed as profligate and inactive on the main issues of the day. He has a long record on this - and spent most of 2021 onwards warning about it.17

But 2021 wasn’t the right time. More specifically, in 2021 people cared about the rising cost of living - a lot. While it was the first 2-3 weeks of the 2021 campaign, both our internal tracking and the Liberal party’s had the Conservatives ticking towards a majority, despite Trudeau calling the election to gain one. In my focus groups, I lost count of the number of people speaking about the rising cost of lumber (and Poilievre was good on this). However, ultimately it was a Covid election, and as a caseload rose in the final weeks of the campaign, the polls tightened.

Takeaway: Put simply, Poilievre might not have been the right candidate in 2021, but being strong on the issue of the day, and not an incumbent - is the closest thing you can get to an unbeatable combination at the moment.

Implications for the UK: Not many. There’s a limit to how much you can ape the right candidate fitting the right time.

The Conservatives cannot escape their record, and anti-incumbency will only take them so far in five years. Perhaps the main lesson here is to take the best vessel for anti-incumbency and anti-institutional politics off the table - as Poilievre has effectively done with the PPC, but the Reform horse has well and truly bolted the stable.

2. The Communications Guru:

Clearly, timing matters, but Poilievre’s success also rests on another critical pillar - his excellent communication.

Poilievre isn’t just good on social media, he’s great. Honestly, just look at his twitter. He’s been doing this for years (see here and here for earlier cuts - the kind of thing that would have gone viral even then). He’s charismatic, speaks well, and has nailed a digital voice that feels native and natural.

There is a school of thought - especially as Westminster absolutely loves the shiny focus on communications and minimal focus on fundamentals - that says that simply doing comms more like Poilievre is the way forward. For evidence - see the awkward attempts across the Conservative leadership election this year to do walk-and-talk videos or copy the slogans.

It would be typical at this point for someone who does policy and strategy to dismiss this - but I won’t. Great comms, done well, is invaluable. Top-tier comms professionals amaze me with their ability to craft and deliver messages across so many channels—a skill I’ll admit I haven’t perfected myself. Without it, politicians fail. Full stop.

However, I think the point here is that it does Poilievre and the CPC a disservice to think that what makes him special, or what can be copied is his approach to communications. First, it’s effective because he has such a clear and concise worldview and diagnosis of the issues. Good comms outputs are downstream of a coherent worldview and a good narrative. Poilievre authentically believes what he is saying - go back to 2020 or before, and you find the same focus on the same issues is present time and time again. That clarity of message comes from true belief, and the effectiveness of his communications and approach, its clarity, and its authenticity follows.

Second, there’s an element of truth to the fact that this is both easier in opposition, and with their platform. Talking to a friend on team Poilievre about how they could help in the UK, they opined that “I’m less useful if there’s no Tax to Axe.” - Put simply, while the CPC’s operation is now close-to-perfect, it’s coming from effective opposition, done well, with a core belief set that sits behind it.

Takeaway: Put another way, pointing at Poilievre’s comms is pointing at a symptom of his success, not a cause.

Implications for the UK: Get good at comms, sure - but focus on the reason that Poilievre is succeeding, not the things that are most obvious. In the same way that better comms wouldn’t have saved Johnson, Truss, or Sunak, it also won’t suddenly fix the right - the Conservative party’s problems go a lot deeper.

3. Pierre - the prophet:

For a long-time I believed that there was a tension between the “incumbency” argument and the “communications” views. Various UK politicians would point at or tweet his videos, I would think “sure, but it’s easy to be anti-incumbent in a high-inflation environment. Who cares?”

In short, I thought it was all fundamentals, and that the good comms stemmed from that. But now, I’m not so sure. I think Poilievre might be a harbinger of what is to come.

That makes me sound like I’m going to start rambling about a wave of populism. I am most definitely not. What I do mean is that Poilievre has for the past few years been stringing together a coherent narrative about why the Canadian state is - broadly speaking - broken.

He raised concerns - about inflation and the broken housing market - well before they were salient. The cost of gas, rent, housing, lumber, none have escaped his ability to wrap inflation into a wider diagnosis of the failures of the Canadian economic model.

But consider this. He hasn’t just pointed at the issues, but also at the culprits. Perhaps one of the most interesting things to go back and read is the argument by Ben Woodfinden - now Poilievre’s Director of Communications18 - where he sketches out what a winning strategy and message for Poilievre would look like.

In the article, he reflects on a 2021 speech by Poilievre called “The Gatekeepers.” At first glance - it seems like standard Conservative fare of attacking regulation and bureaucracy, but it quickly morphs into something more interesting. As Ben sums it up - “In the speech, Poilievre basically outlines how powerful interests and voices exercise their influence at the expense of the broader society, including those who lack similar pedigree or connections.”

Again - this might seem fairly normal populist rhetoric - but to treat it as such does it a disservice. What he does in the speech, and what Ben articulates very well - is the way that Poilievre combines his worldview - on deregulation, bureaucracy, red tape, and other bread and butter issues - with the wider problems facing Canadian society. In doing so he creates a very consistent worldview of how regulation and gatekeepers are holding back Canadian society, and created what Ben described as “a perfect storm message. It scratches the itch of different parts of the conservative coalition.”

Let’s note a few things that make this very compelling here. I think there are three:

First - this is authentically Poilievre. It’s a message he has been pursuing variations of for a long time - tied to a very consistent and coherent worldview. What the language of “Gatekeepers” has done has sharpened it and given it focus.

Second - it speaks to the major issues that Canadians are facing right now. High cost of living, and an incumbent government that has presided over the period of inflation in an often haughty way.

Third - it speaks to the character of the Liberal party specifically, and their status as Canada’s natural party of government, and the political embodiment of its ruling class and institutions.

The latter point is absolutely vital, and makes difficult reading for UK Conservatives. When Poilievre speaks about elites or the gatekeepers, what he is really doing is signalling the unaccountability of Canada’s ruling class, and the widespread dissatisfaction with them. From a UK context it’s easy to forget, but the Canadian Liberal party is effectively Canada’s business liberal party - as if bits of New Labour and Tory moderates in London, the Shires, and the Metro centres clubbed together for social liberalism, business-friendly government, and a large dose of political professionalism and “evidence-based” policy.

Put another way - they are Canada’s natural party of government, with all of the strengths and weaknesses that this brings. When its opponents speak of it - they speak of a party that they think is arrogant, out of touch, aloof. It’s a party that genuinely thought nothing of bringing back a globetrotting academic to run to be Prime Minister, and is reportedly considering repeating the trick with Mark Carney. It’s a party that has an awful lot in common - culturally and institutionally - with the civil service that it governs. Justin Trudeau is, in many ways, its personification.

Poilievre’s magic lies in how his message weaves together Trudeau’s perceived flaws, economic discontent, institutional distrust, and core Conservative themes. His worldview isn’t just authentic—it hits every Liberal pain point at once. In Ben Woodfinden’s words - it’s the “perfect storm.”

To me, that’s more than a happy accident - it reflects that he is the only politician in Canada talking systematically about the issues Canada faces, and how his worldview will address them from first principles. To elaborate, most Western democracies are facing combinations of the same challenges - institutions that are manifestly failing to deliver, anaemic growth, spiralling living costs, uncontrollable immigration patterns, liberal overreach across an array of social issues, and a creaking state machinery that seems to put citizens last.

That these have an electoral impact, and that they broadly help the “right” is hardly surprising - see the 2016 and 2024 US elections. But they haven’t really translated - so far - into a coherent programme of government. In Poilievre I think we see both a coherent political diagnosis of Canada’s problems, and crucially the first coherent view of what the answers the centre-right gives should be.

Yes he has tapped into the same sentiments that have delivered a Republican resurgence in the US, and earlier victories in Australia and the UK, and yes he’s in the right place to be heard. But he wouldn’t be making the ground he is without that clarity and vision about the “Gatekeepers”. Everything else - the machine, the communications, the videos - is downstream of that, and works because the worldview is so clear, so consistent, and so easy to understand.

So what are the lessons for UK Conservatives?

Well, first - they’re not currently the vessel for this sort of politics. The UK’s Reform party is tapping into public dissatisfaction with the political system, mirroring the anti-establishment sentiment Poilievre has harnessed. Yet, while they share this ethos, the similarities largely end there. Reform (so far) lacks the clarity, leadership, and cohesive narrative that underpin Poilievre’s success. But that probably won’t last for long, and time is ticking.

On the plus side, Kemi Badenoch offers a rare voice within the UK Conservatives, willing to speak candidly about systematic failings in British institutions with clarity and conviction. Her critique of state ideology and institutional inefficiency is promising and aligns with the broader mood of discontent. But her real problem is the party’s legacy and history. Not only was it holding the parcel when the music stopped, but it is also the natural party of government, and hardly the vessel for an anti-politics form of politics. She may well be the right leader, in the wrong party, at the wrong time.

Takeaway: The lesson from Poilievre is clear: his success is rooted in a compelling political vision that addresses systemic issues and speaks directly to voter frustrations. This clarity of purpose drives everything else—communications, tactics, and policies.

Implications for the UK: Poilievre’s success stems from more than just circumstances or style—it’s his ability to diagnose systemic issues and craft a narrative that resonates.

For UK Conservatives, the challenge isn’t just to copy his approach but to work out their authentic story about the state’s failure and how they can quickly change it. Without that, even the best tactics won’t save a party weighed down by 14 years in power and the baggage of incumbency.

A note:

I’m taking advantage of not speaking for another organisation to write about a few passion areas. Canadian politics is one, and I’m also planning a few other pieces on policy, politics, etc. If you liked this then please do subscribe to receive the next one.

Reader - it has already started.

Michael Ignatieff was - regardless of how impressive he is on paper - an incredibly flawed candidate who didn’t match the mood of the country. Don’t believe me? Watch the adverts the CPC ran.

I had the pleasure of working with some of the people involved in this in a later campaign. To this day it’s one of the pieces of work they’re most proud of.

I remember this distinctly as only one other student in my class at University of Toronto was upset with this outcome… we drank a lot that evening.

It’s worth noting that this includes unorthodox decisions like literally giving voters (in 2021 - pensioners, now most workers) cash directly. This is quite shameless, and one of the causes of his current issues with his former Finance Minister.

It is worth noting that Freeland was often talked about as a successor. In this context some space between herself and Trudeau is not unhelpful.

It’s hard to see how this happens with the NDP saying they’ll vote against the Government. The Liberals also beginning to run election ads suggests that the end is nigh.

A polling/data firm that I was part of, and Topham Guerin. Notably I did not work on the 2019 campaign, but was working with people who did, and knew far too much about Canadian politics.

Look how that turned out…

Declaring an interest - I ran Tom Tugendhat’s campaign.

For those who do not study Canadian politics closely - think Texas but Canadian. This is extremely imprecise and unfair on both, but I’m using it for a quick explanation. Essentially think Conservative provinces with large natural resources wealth, and a heavy Conservative skew.

There is also plausibly heavy Chinese interference in the election campaign - but ultimately a c. 10 seat difference wouldn’t have changed the overall outcome significantly.

We can get into the leadership election system the CPC uses another time, but in short points are allocated through riding votes.

My name is not on it, but I promise this is not me being dishonest - it’s because it was deemed that running a leadership campaign and publishing the election review simultaneously was perhaps not the right thing to do, and so I stepped away from doing the latter after a lot of work.

My wife posited Modi as the exception - I am not an expert in Indian politics, but even in this case Modi was whittled down away from an absolute majority for the BJP.

For example, Atlantic Canada and parts of rural Ontario. An under-noticed element of the 2021 election is quite how much ground the CPC gained here. Based on polling in the last few weeks we diverted significant resource to Atlantic Canada, and the early results threw the press for a loop, but ultimately not enough seats were converted in and around the GTA to make up for it.

And a friend of friends - we have never met, but I have followed his writing for a long time and suggest you do too. He obviously writes less publicly now - but tweets at: https://x.com/BenWoodfinden